Are Aviation’s Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) needs sustainable?

We need to address the criticism that we are asking for more than our fair share

In an Arabian Travel Market panel on sustainable aviation chaired by Shashank Nigam, Boeing's Brian Moran noted that there are 23,000 commercial aircraft in the skies today.

That number will only increase. As these aircraft typically have a lifespan of 30 years, taking us beyond the industry’s 2050 net zero target date, he felt that aviation's net zero plans will need to rest heavily on Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). In fact, Boeing sums up its whole net zero strategy as “SAF And.”

Of course, SAF currently has issues around availability (there simply isn't enough of it) and cost (it's more expensive than normal jet fuel).

But there's another important issue around SAF – its production is incredibly resource-intensive.

A report published in the Science of Total Environment by academics Susanne Becken, Brendan Mackey and Dave Lee looks at this in more detail.

The report starts by noting that a dozen major aviation net zero road-maps rely heavily on SAF.

However, this is a problem.

"The scaling up of SAF to not only maintain but grow global aviation is problematic as it competes for land needed for nature-based carbon removal, clean energy that could more effectively decarbonise other sectors, and captured CO2 to be stored permanently."

In particular, they estimate that industry decarbonisation could mean the use of 9% of global renewable electricity (for E-Fuels) and 30% of sustainably available biomass (for biofuels) by 2050.

That ties in with other studies that have been published.

Last year, Arizona State University released research estimating that the US aviation industry could be decarbonised via the large-scale planting of acanthus (or silver grass) as a feedstock. To do so, however, would require land use equivalent to the state of Wyoming.

Similarly, European Venture Capital firm World Fund came out with a knowledge paper in December 2022 claiming that even replacing 8% of Europe’s aviation fuel with E-Fuels by 2040 would require the equivalent electricity consumption of the Netherlands or Sweden.

Solar Fuels and process efficiency

So what’s the answer?

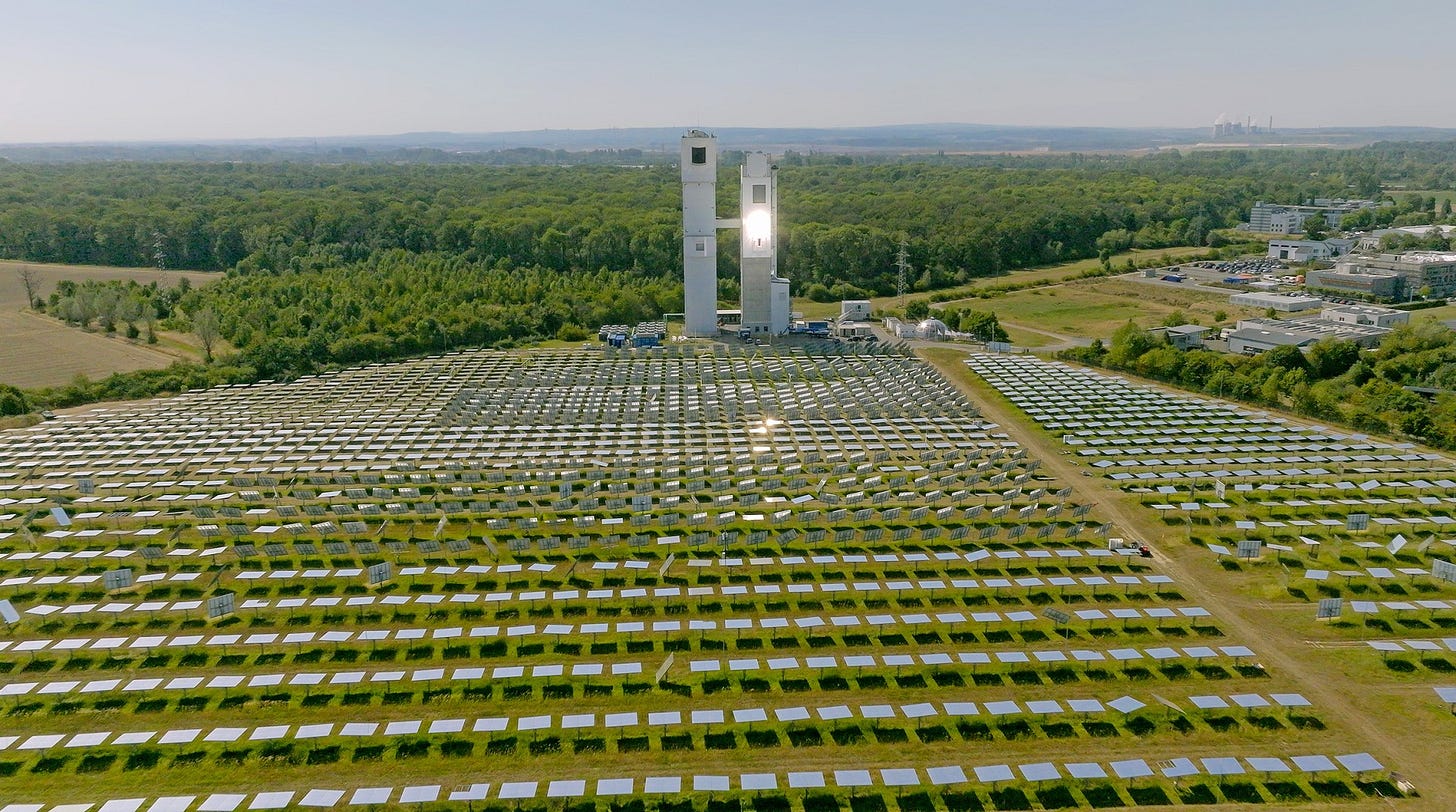

The World Fund paper gives a few clues as to possible solutions. One is the production of solar fuels, which use sunlight to electrolyse hydrogen from water.

An example is the Swiss company Synhelion, which has a partnership with the Lufthansa Group and has a pilot plant in operation called ‘Dawn.’

That, in turn, is an opportunity for sun-rich countries around the world.

For instance, the United Arab Emirates, the host of this year’s COP28 climate summit, has an ambitious goal of replacing as much as 73% of the country’s jet fuel needs with fuel made from renewable (solar) energy.

Then, several companies are looking at making the process of producing E-Fuels more efficient.

New York’s Air Company, which counts JetBlue and Virgin Atlantic as customers, has patented a single-step process to make E-Fuels.

This contrasts with an almost 100-year-old process called Fischer Tropsch, which has traditionally been used to make synthetic fuels.

Fischer-Tropsch is both energy-intensive and wasteful.

In a talk last year, Air Company’s Co-Founder and CTO Dr Stafford Sheehan said that Fischer Tropsch has an energy efficiency of around 20-30%, meaning that for every 100 units of energy that are input into a reactor, only 20 units of energy are output in the form of liquid. The other 80 units are wasted.

Instead of 20%, Air Company says it achieves 50% energy efficiency.

Meanwhile, Air Company says its process efficiencies result in lifecycle emissions reductions of up to 97%, not 80%, which is the number normally quoted for SAF.

Aviation as luxury emissions?

The resource issue is one that environmental groups are picking up on with increased frequency.

They ask why the airline industry should be first in the queue over other sectors such as (e.g.) road transport, shipping or heavy industry.

Pointing out that most people don’t, in fact, fly, their view is that a lot of air travel is what they call ‘luxury emissions.’

An economic and social case can be made for why aviation should benefit from land and/or renewable energy use. In particular, it provides a way for emissions to be decoupled from growth, opening up mobility via air travel to even more people.

Meanwhile, much of the Global South is keen on the enormous GDP potential of areas such as green hydrogen.

But you rarely hear industry spokespeople address this, talking instead about SAF as a panacea that will (eventually) solve the industry’s greenhouse gas problem.

However, in future, we are going to have to answer the questions - What’s our fair share? Are we asking for more than we are entitled to? And how can that ‘ask’ be reduced?