Can Prometheus deliver fuel from air at fossil fuel prices?

Backed by Maersk and BMW but doubted by scientists, Prometheus Fuels is betting everything on a technology with many sceptics. Who’s right?

A black Mustang hurtles across the desert. "FUEL FROM THE AIR," the screen proclaims, as if it were a film opening. But this isn’t fiction. It’s the homepage of Prometheus Fuels, a startup with seemingly outlandish claims that is equal parts revolutionary tech and Hollywood spectacle.

With electric guitar riffs scoring their demo videos and CEO Rob McGinnis claiming they’ll undercut fossil fuels without subsidies, Prometheus is not just selling fuel, it’s outlining one of the most entertaining stories in climate tech.

That storytelling sets them apart.

While other companies talk about decarbonisation pathways and regulatory requirements, Prometheus offers pulp sci-fi fantasy: Modular reactors named after Faraday; bold, colourful storytelling; classic cars and Harley-Davidsons powering through Californian towns and deserts.

But underneath the audacious narrative, what’s the technology? And do the company’s eye-opening claims stand up to scrutiny?

Air, water, electricity, and ambition

Prometheus is fundamentally a synthetic fuels company. But according to Rob McGinnis, his company stands alone in doing things very differently.

Referring to other companies in this sector, he told us:

"We don't do anything like what they do. We're the 0.1%. The 99.9% of everybody does Fischer-Tropsch or something like it... Fischer-Tropsch just never pencils out. It's just way too expensive."

He was referring to the standard playbook under which most Power-to-Liquid (PtL) fuels companies operate. They start with green hydrogen made from renewable energy with CO₂ and then process it via the Fischer-Tropsch method, a technology that recently celebrated its 100th anniversary. This energy-intensive process results in fuel typically 5x or so more expensive than the fossil fuel equivalent.

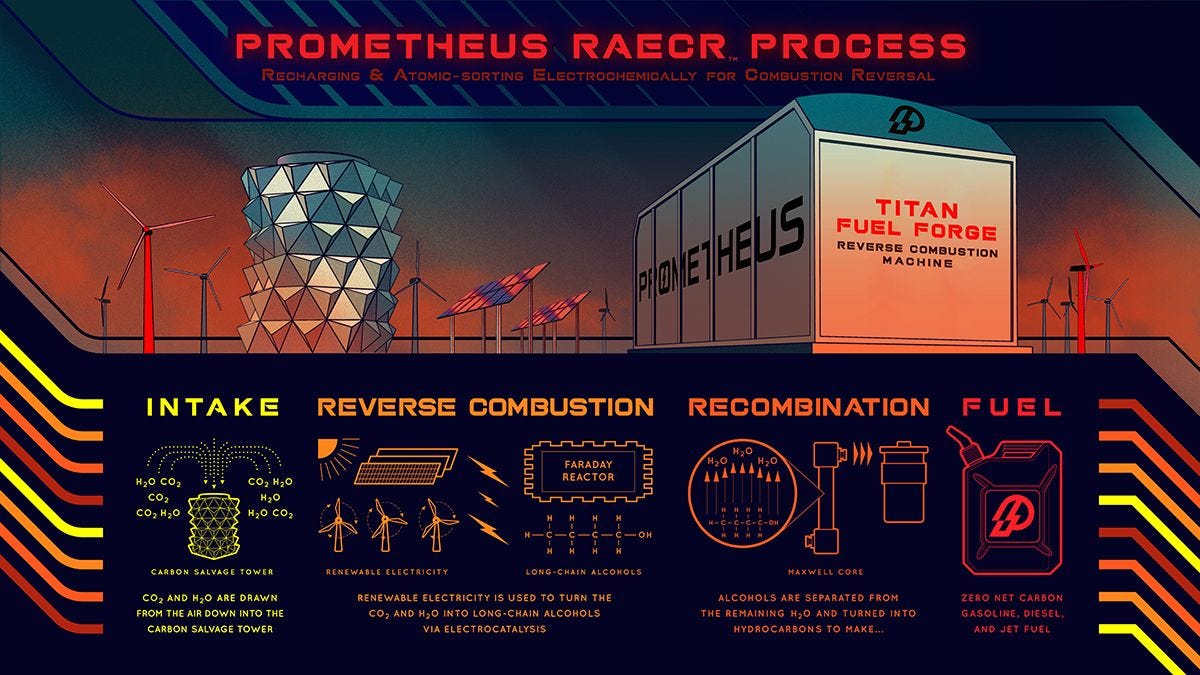

Prometheus integrates direct air capture with their proprietary "Faraday reactor", a hydrocarbon electrolyser that produces hydrocarbons directly rather than just hydrogen or carbon separately. The key breakthrough is coupling these systems to avoid the expensive CO2 desorption step that traditional direct air capture requires.

Instead of using conventional adsorbents that require heat and energy to desorb CO2, Prometheus uses a cooling tower-like system with spray nozzles that absorb CO2 directly into a high-pH water-salt electrolyte solution.

The system operates at room temperature and atmospheric pressure using plastic stacks rather than expensive alloys or platinum group metals, making it significantly cheaper than high-pressure, high-temperature conventional processes.

The technology is designed to be modular and location-independent. McGinnis explained that their approach fundamentally differs from competitors who need billion-dollar centralised plants: "The great thing about our approach, this modular approach, where it's all stack-based, is that once you have a full-size stack built exactly the way you're going to build it... anything else you do is just packaging.

This modularity enables geographic flexibility that McGinnis sees as a crucial advantage. Prometheus can deploy wherever solar resources are cheapest.

"We don't need a grid connection... we can go out in the middle of Arizona, Nevada, Texas. And as long as you have some clear land, you can just start building solar and using it directly."

Here, it’s worth noting that modularity is not unique to Prometheus. It’s core to how the German e-fuels company INERATEC works. They recently opened up Europe’s largest PtL fuel plant outside Frankfurt.

'It's laughable': The critics weigh in

Not surprisingly, Prometheus has its share of sceptics who cast doubt on the company's claims.

In 2022, MIT Technology Review published a critique titled "This $1.5 billion startup promised to deliver clean fuels as cheap as gas. Experts are deeply skeptical."

The piece raised fundamental questions about whether Prometheus could achieve the dramatic cost reductions it claims. "It's laughable," Eric McFarland, a professor of chemical engineering at UC Santa Barbara, told MIT Technology Review. "It's the tech bubble again. People are putting money into lots of things that ultimately won't ever work, and this is one of them."

The MIT article challenged multiple aspects of Prometheus's business model. It questioned the company's solar cost assumptions. The piece also alleged that some prominent climate-focused venture capital firms had not invested in the company, with sources suggesting the cost and technical claims seemed "highly unlikely."

Finally, the article questioned chemistry claims. Sean McCoy, an assistant professor at the University of Calgary, told MIT Technology Review that while the process was "technically possible," academic groups working on similar electrochemical processes for converting CO2 to alcohol had produced "very low yields."

McGinnis defended his company against these criticisms, telling MIT Technology Review that sceptics "would be convinced if they had access to our data, models, and methods." He explained that the company had limited information sharing to protect intellectual property, particularly with venture firms that had invested in competing companies, asking such firms to rely on technical due diligence from third-party consultants instead.

In our interview with McGinnis, he suggested that much of the scepticism was driven by competitive interests rather than genuine scientific concerns: "Most of the doubt is coming from our competitors through various communication channels. There have been articles where our competitors have been interviewed and not identified as our competitors."

He also emphasised the inherent doubts that any disruptive startup faces: "Startups just face scepticism as a base layer... for us to go and say, hey, we're going to do this for price parity, which means we're going to be one-seventh or one-eighth the cost of all our competitors... that strikes people as being miraculous."

Why Maersk and BMW are betting big

It’s worth noting that McGinnis is a Yale-trained engineer with a track record in water technology and membrane development. Before founding Prometheus, he co-founded desalination startup Oasys Water and nanotechnology company Mattershift, demonstrating experience in bringing advanced materials to market.

Meanwhile, sophisticated industrial players like Maersk and BMW, with their own technical teams that would have done a reasonable amount of homework, have invested in Prometheus and sit on the company’s board. This suggests that the technology at least merits consideration.

Maersk, in particular, is eyeing green methanol for its new vessels as the maritime industry faces mounting pressure to decarbonise. This is one reason why methanol is the company’s first commercial product.

According to McGinnis, “methanol initially is a really good, versatile molecule because it can be turned into gasoline, diesel and jet."

This versatility matters enormously for Maersk, which has been pioneering methanol-powered container ships and needs reliable supplies of carbon-neutral fuel. The shipping company has committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 and has already launched several methanol-powered vessels, making Prometheus's promise of cost-competitive green methanol particularly attractive.

In the aviation industry, meanwhile, both Boom Supersonic and American Airlines have signed offtakes.

The moment of truth

Within 12–18 months, Prometheus will face its crucial commercial test. While the company has missed previous deadlines — a common pattern across climate tech as companies grapple with scaling complex energy technologies — they now claim to have reached commercial readiness and have sold out their first decade of production.

Perhaps McGinnis really has stumbled upon something revolutionary that the entire e-fuels industry has missed — a way to bypass the constraints that have made synthetic fuels prohibitively expensive.

Or perhaps the critics are right, and Prometheus is simply the latest in a long line of startups promising to solve intractable chemistry problems with venture capital and marketing prowess.

McGinnis, though, stressed at the end of our interview: "I just want to emphasise that it really is a distinct technology. It's not like everybody else."

Time will tell. For now, the black Mustang keeps racing through the desert, fuelled by ambition and questions that commercial-scale deployment will ultimately answer.