Carbon offsets have failed. What's next for aviation?

With CORSIA facing a supply and credibility crisis, a new wave of Direct Air Capture innovators offers a more scientifically sound path forward.

In a nutshell

A 25-year experiment in carbon offsetting has failed: A major new academic study finds that almost all offsets to date have delivered little or no real climate benefit, “riddled with intractable problems” such as non-additionality, impermanence, and double counting.

Aviation is the case study for that failure: Airlines have paid as little as €4 per tonne of CO₂, with offsets baked into CORSIA, creating a looming credibility and compliance crisis: just 15.8 million eligible credits exist against 144 million needed by 2028. Almost all come from Guyana, with questionable deforestation baselines.

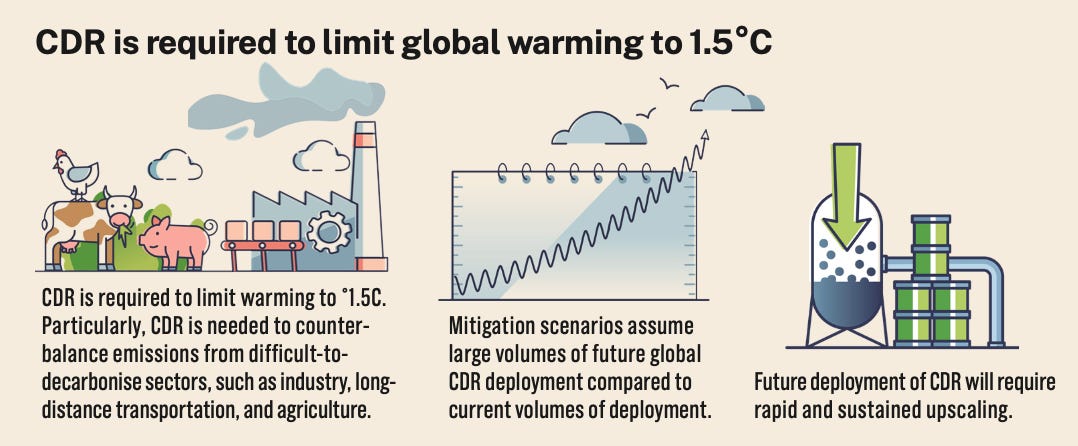

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), including Direct Air Capture (DAC), offers a credible and verifiable path forward: It remains expensive — typically over $300 per tonne. Still, more than 800 companies are innovating to make it scalable and cost-competitive.

Offsetting has “almost entirely failed”

Over the past few years, carbon offsets have taken one reputational hit after another. We’ve seen exposed claims, failed projects, and accounting loopholes. Most notably, an investigation in 2023 found that more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets approved by the standards body Verra and purchased by major organisations, including airlines, were likely “worthless.”

Now comes what could, or at least should, be the final blow — and a signal to shift from questionable offsets to permanent CO₂ removal.

A landmark study published this week in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources by researchers at the University of Oxford and the University of Pennsylvania concludes that 25 years of offsetting have “almost entirely failed” to deliver genuine emission reductions.

This isn’t about a few bad actors and rogue schemes. The authors, Dr Joseph Romm, Dr Stephen Lezak, and Dr Amna Alshamsi, identify structural flaws, including:

Non-additionality: credits issued for projects that would have happened anyway.

Impermanence: carbon re-released through fires or land-use change.

Double-counting and gameability: systems that reward creative accounting more than genuine abatement.

The authors’ prescription is clear: “These junk offsets, the ones not backed by permanent carbon removal and storage, are a dangerous distraction from the real solution to climate change, which is rapid and sustained emission reductions.”

In short, the Oxford–Penn team calls for the phase-out of nearly all offsets, except those linked to high-integrity, durable carbon removal and storage with long-term measurement and verification (MRV). If the carbon isn’t physically taken out of the atmosphere and locked away for centuries, it shouldn’t count.

The Potsdam warning

Their conclusion echoes a separate warning from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, published in Nature, that low-integrity offsets are actively undermining decarbonisation by flooding markets with cheap, paper credits that depress real carbon prices and delay genuine emissions cuts.

Potsdam’s authors argue that such “hot-air” credits don’t merely distort markets; they delay the fossil-fuel phase-out. The institute recommends that if any credits are used, they should be limited to durable removals while countries strengthen domestic carbon pricing rather than outsourcing responsibility abroad.

A Carbon Market Watch study clearly illustrates the problem: some airlines were paying as little as €4 per tonne of CO₂, which is far too low to drive meaningful mitigation.

The CORSIA crisis

Offsets may have bought us time, but not progress.

Yet, as the credibility of carbon credits collapses, aviation remains structurally tied to them through the ICAO-approved programme, CORSIA, which was built on the assumption that buying credits would be a straightforward and cost-effective way to mitigate the industry’s climate impact.

That logic now looks questionable. To start, there is a supply and demand problem. According to Sylvera, the current pool of eligible credits stands at just 15.84 million, against the potential demand of 144 million by January 2028.

But it gets worse. As of June 2025, almost all CORSIA-eligible credits came from avoided-deforestation schemes in Guyana, rewarding “savings” against predicted forest loss.

Those predictions could well be inflated. A 2009 McKinsey report used to justify Guyana’s baseline assumed roughly 4% forest loss per year; later, independent assessments put the actual figure near 0.2%.

The country’s ART-TREES system has issued tens of millions of so-called High Forest, Low Deforestation (HFLD) credits, now eligible for airline use. But analysts warn that many of these are “accounting artefacts” created by generous baselines rather than measurable carbon savings.

The reality is that CORSIA’s rules were written for a different era.

Regulators’ innate caution means that newer technologies, such as DAC, mineralisation, and engineered storage, remain excluded, leaving airlines stuck with a 2016-vintage compliance model just as offset credibility collapses.

The market we need

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report shows that pathways compatible with the Paris Agreement require multi-gigatonne CDR by mid-century, often cited as roughly 10 Gt CO₂ per year.

However, the carbon removal market remains relatively small. The Wall Street Journal has called it a “$250 billion opportunity that almost no one is interested in.” Barely 175 million tonnes of removal credits have ever been sold.

Microsoft alone accounts for more than a third of all engineered removals, with Stripe, Google, and McKinsey making up most of the rest.

To its credit, aviation is starting to engage. IATA’s April 2025 fact sheet calls carbon-dioxide removal “critical to offsetting residual aviation emissions that cannot be eliminated by other means,” urging investment in both conventional (forestry, soil carbon) and novel (biochar, BECCS, DAC) methods.

Moreover, airlines including British Airways, Lufthansa, American, and United have already partnered with DAC firms or signed early-purchase agreements.

Innovations in Direct Air Capture

CDR, especially DAC, remains expensive, often exceeding $300 per tonne, because extracting 420 parts of CO₂ from a million parts of air requires enormous amounts of energy.

But innovation is accelerating. In 2024, Bloomberg NEF identified more than 800 companies active in the CDR space, and a new generation of innovators is starting to emerge.

Paris-based Norma, featured in our DAC Disruption Explainer and on the Signal podcast, has developed a supercapacitor-inspired system that reuses most of the energy needed for each capture cycle, a ten-fold improvement over conventional DAC.

NEG8 Carbon (Ireland), RepAir (Israel), Sirona (Belgium), and Carbyon (Netherlands) are likewise driving costs down through electrochemical processes, modular design, and mass manufacturing.

These firms aren’t building vast industrial plants. Instead, they’re producing smaller-sized units that can be mass-manufactured like consumer electronics. If successful, this modular approach could make DAC viable for both permanent carbon removal and CO₂-based sustainable aviation fuels (e-fuels).

It’s a far more compelling vision than continuing to buy low-integrity offsets from halfway across the world.

Closing the door

Carbon offsets have lulled industries, aviation included, into a false sense of progress. The next 25 years must look different: decarbonisation first; durable, verified removals second. And those need to be permanent, science-based, and high-integrity.