Rethinking aviation's path to Net Zero: the carbon removals approach

How direct carbon removal could help airlines accelerate the path to true zero emissions.

Executive summary

For aviation to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, an alternative to the current Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) strategy is emerging: combining conventional jet fuel use with direct carbon removal from the atmosphere while accelerating the development of 'true zero' technologies.

An analysis by Robert Höglund shows that capturing and storing CO2 uses 7x less electricity than producing e-fuels, suggesting direct storage is more efficient.

Major airlines such as British Airways are already getting into carbon removal credits. Others include Lufthansa partnering with Climeworks, and American Airlines with Graphyte.

Proponents argue that this approach could help airlines skip costly interim steps and focus on developing zero-emission technologies.

The carbon removal industry is experiencing rapid innovation, with Bloomberg identifying over 800 firms in the space. Experts predict consolidation like the early automotive industry while maintaining some regional players.

The current landscape

The challenge is considerable: reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 comes with a $4.7 trillion price tag. The industry's current orthodox solution centres on SAF, particularly synthetic alternatives to conventional jet fuel.

However, this approach faces significant resource and cost hurdles that could ultimately slow progress toward genuine zero-emission technologies.

Another solution is now gaining traction: continuing to use conventional jet fuel while permanently removing carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere. This approach, coupled with the accelerated development of new 'true zero' technology, could challenge the current SAF-centered strategy.

This comes as major carriers are already testing the carbon dioxide removal (CDR) waters. British Airways has committed over £9 million to purchase carbon removal credits over six years, positioning itself as the largest airline purchaser globally. Lufthansa Group has partnered with Climeworks through 2030, while American Airlines has agreed to purchase credits equivalent to 10,000 tonnes of carbon removal from Graphyte.

One high-profile advocate, carbon removals expert Robert Höglund, spoke to Sustainability in the Air to make a compelling case for why this might offer a more efficient path forward.

The economics of clean flight

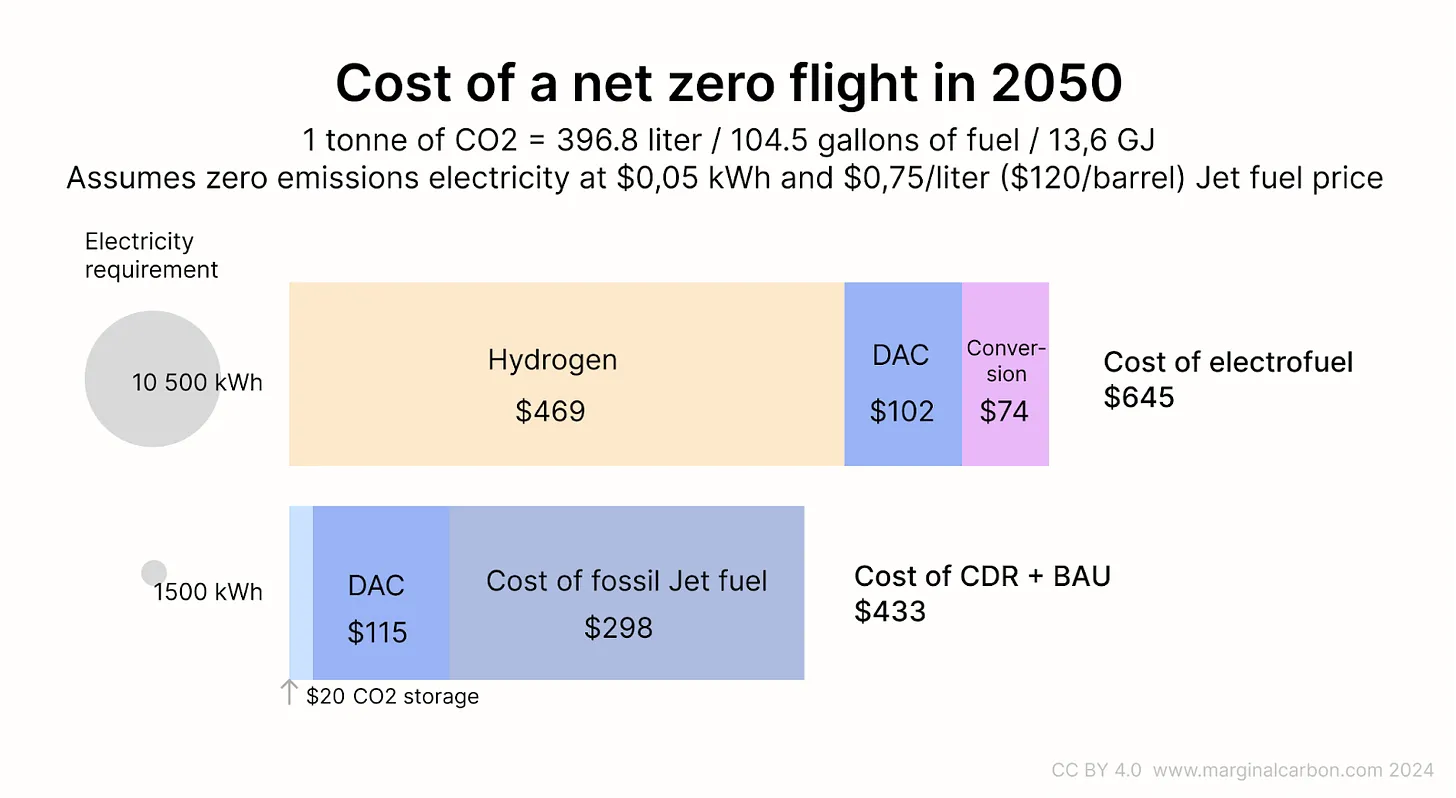

Robert Höglund runs CDR.fyi and the Milkywire Climate Transformation Fund. Höglund has argued in an analysis that producing e-fuels – synthetic alternatives to jet fuel made from CO2 and 'green' hydrogen – requires seven times more electricity than simply capturing and storing the same amount of CO2 while continuing to use conventional fuel.

Höglund says that replacing just one-third of current aviation fuel with e-fuels would demand over 2,500 terawatt-hours annually – 10% of global electricity consumption. Carbon removal would need just 410 TWh.

Though some startups believe they can significantly disrupt the sector, Höglund’s analysis shows that e-fuels only reach cost parity with conventional fuel plus CDR under specific conditions: when fossil fuel prices significantly increase or electricity costs are exceptionally low.

With Middle Eastern oil produced at $20 per barrel – a quarter of current market prices – the economic advantage of conventional fuel could persist.

The resource dilemma

Further research published in Science of the Total Environment found that decarbonising aviation through SAF could consume 9% of global renewable electricity for e-fuels and 30% of sustainably available biomass for biofuels by 2050.

That resource intensity – for e-fuels in particular – has led to criticism. Speaking to the Land and Climate podcast, Finlay Asher, a former aircraft engineer and co-founder of Safe Landing, called e-fuel-powered flights "probably the most inefficient thing you could do bar putting it [e-fuel] into a rocket and sending Jeff Bezos into outer space.”

The innovation race

The carbon removal industry remains in its infancy. While Bloomberg has identified over 800 firms in the broader carbon removal space, permanent carbon removals are expensive. Current direct air capture costs exceed $500 per tonne—far above the U.S. Department of Energy's $100 benchmark.

"Everything is more expensive than you think when you do it in reality," Höglund acknowledges. "There's so many things that you couldn't really model." However, he remains optimistic about future cost trajectories, suggesting that both bioenergy with carbon capture (BECCS) and direct air capture will come down considerably in price within a decade.

The innovation landscape is evolving rapidly. Among the roughly 230 companies evaluated by Milkywire's Climate Transformation Fund last year, approaches range from traditional direct air capture to creative solutions like repurposing old mine lakes for carbon storage. Some companies, like RepAir, claim they can already break the $100 threshold, while others are exploring entirely new approaches.

Höglund sees parallels with the early automotive industry. "How many car manufacturers were there 100 years ago? It was like a thousand," he notes. "You'll see many just going out of business because they couldn't raise series A or B funding rounds, or bigger players acquire them."

He envisions different paths for various carbon removal technologies. The direct air capture segment will likely consolidate into a handful of global players, similar to the telecom or automotive industries. Other methods, like biochar, might remain more regionally distributed due to their reliance on local biomass sources.

Accelerating to zero

The University of Cambridge's Aviation Impact Accelerator recently published a five-year roadmap designed to bring aviation to net zero. The roadmap outlines five distinct stages:

Improving system efficiency

Developing sustainable fuels

Transforming infrastructure

Advancing new aircraft technologies

Achieving zero-emission solutions

Carbon removal advocates suggest their approach could help airlines leapfrog through several of these intermediate stages. Rather than following the sequential path through SAF development and infrastructure transformation – which requires massive investment in fuel production facilities and supply chains – airlines could use carbon removal as a bridge technology while focusing resources on developing truly transformative solutions.

This would mean investing in next-generation technologies like blended-wing aircraft developed by companies like JetZero, hydrogen propulsion systems, and electric aircraft for shorter routes.

"The industry needs to be technology-agnostic," Höglund emphasises. "Open up for CDR, permanent carbon removal combined with continued use of conventional jet fuel, and then let market forces determine what wins the day."

The business model

CDR does present a significant economic challenge, with many airlines still relying heavily on cheap carbon offsets – which averaged just under $7 per carbon tonne in 2023 despite mounting criticism over their effectiveness (though in the EU, ETS prices are at just under 70 euros per carbon tonne). However, Höglund suggests the cost issue could be overcome through creative approaches.

Airlines could find immediate savings by storing CO2 rather than investing in synthetic fuels. Beyond this, Höglund proposes innovative financing structures: "You should think about how to share the cost with your customers. You have a lot of business customers with whom you could make deals, like a tri-party deal between the CDR supplier, yourself, and the customers."

Meanwhile, while critics argue this approach could allow aviation to delay genuine decarbonisation, Höglund emphasises that specificity is key:

"When plans are concrete about exactly how much conventional fuel will remain and how it will be matched with permanent carbon removal, it's harder to use CDR as a fig leaf for inaction."

He predicts that ground transport electrification will eliminate much of oil consumption anyway. "We're not going to have all oil companies reduce their emissions, [instead] we're going to have fewer oil companies," he suggests.

"The remaining ones will compete to be the last standing, potentially selling 'net-zero oil' bundled with carbon removal." This transformation is already beginning, with companies like Occidental Petroleum heavily investing in carbon removal through its subsidiary 1PointFive.

Our take: Should we consider a hybrid approach?

While the aviation industry has largely committed to the SAF pathway, with the UK and EU promoting the use of e-fuels as part of this, a hybrid approach combining these strategies with Robert Höglund's CDR-centric solution may offer a more balanced and effective pathway to net-zero emissions.

By prioritising the most efficient synthetic fuel projects and complementing them with robust CDR strategies, we could optimise the allocation of renewable energy resources across sectors. This approach could focus E-fuels investment on the most cost-effective and energy-efficient solutions while CDR addresses residual emissions.

The key for industry leaders will be maintaining the flexibility to adapt as technologies evolve and new solutions emerge.

Our latest report explores the potential of carbon dioxide removal (CDR), the challenges it faces, and why it could be the breakthrough aviation needs. Download the full report for free here.