Hydrogen is the key to sustainable aviation: Cranfield Aerospace Solutions

CAeS plans to create a “little Airbus” specialising in Hydrogen aircraft.

Jenny Kavanagh, Chief Strategy Officer of Cranfield Aerospace Solutions (CAeS), underscores the vital role hydrogen will play in the future of sustainable air travel, stating it is “the only solution for aviation that exists today, as far as we can see.”

CAeS, a company spun out of Cranfield University in the UK in 1997, announced this year that it would merge with Britten Norman, a manufacturer known for producing short takeoff and landing (STOL) aircraft such as the Islander. Their shared objective? To develop true-zero aircraft with no CO2 emissions.

In fact, Kavanagh envisions CAeS as “a little Airbus” in the long run, focusing on hydrogen-powered aircraft with seating capacities of up to 100 passengers. The initial phase of this endeavour, titled “Project Fresson”, involves retrofitting the nine-seat Britten Norman Islander with hydrogen-electric powertrains.

A demonstrator aircraft is set to begin a test flight programme in 2024, with the view to certifying the hydrogen version of the Islander for commercial entry into service in 2026.

In settling upon hydrogen, Kavanagh emphasises that the company’s sole interest was to find the most effective solution for its aircraft: “We’re not technology evangelists. We are an aircraft company, and we look for the best technology for the aircraft that we are looking at.”

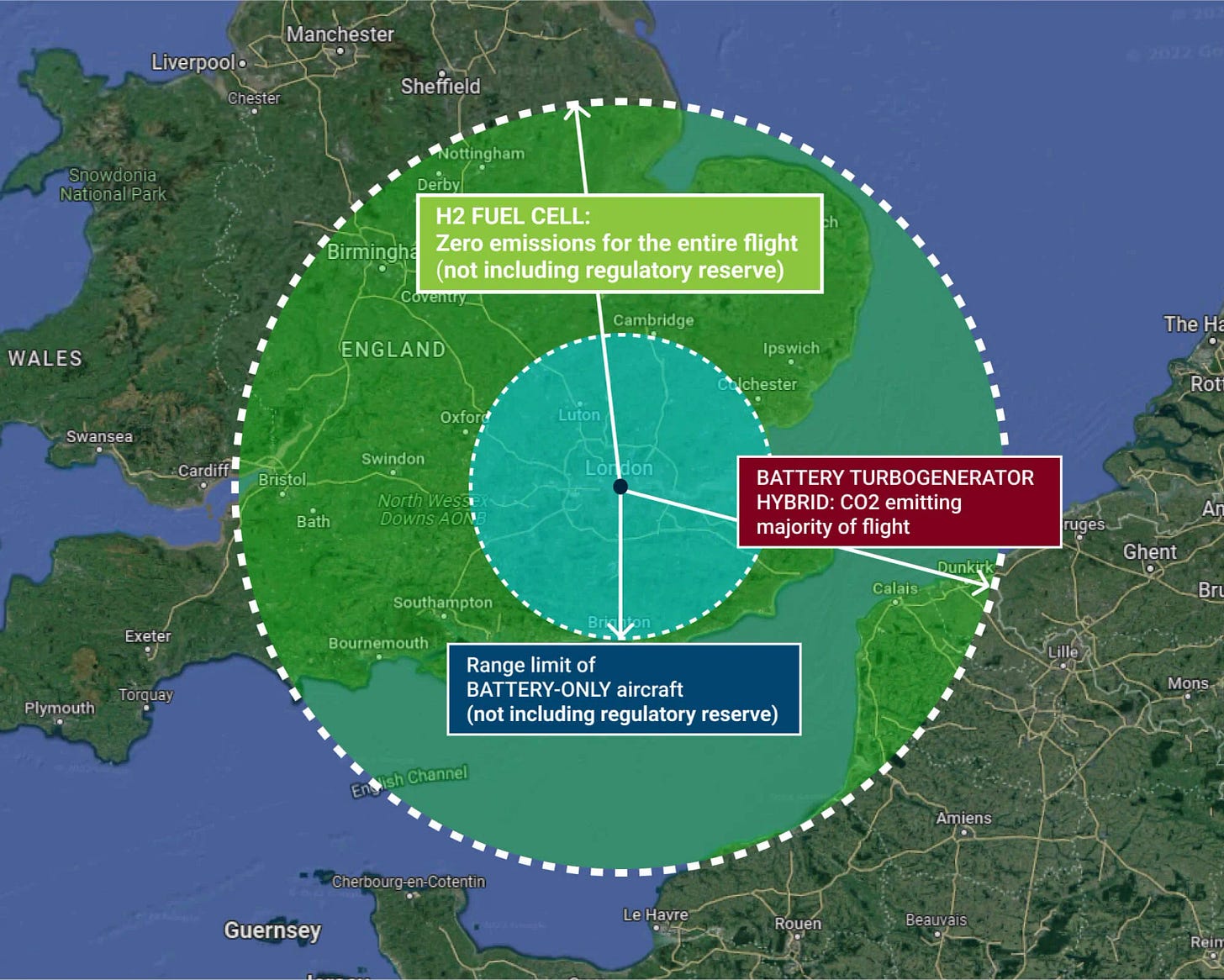

As a result, the CAeS team explored battery-electric technology first. Unfortunately, the conclusion was that “with a retrofit of our nine-seat Islander you get about 20 minutes of flight, which is absolutely pointless.”

The next step was to look at the hybrid-electric route. There, too, were numerous limitations.

Cranfield Aerospace Solutions finally turned to hydrogen, realising that the technology had progressed significantly since the company first evaluated it.

“It was unbelievable how much it had accelerated”, said Kavanagh. “At that point, we thought it’s no longer a technology of the future; it’s pretty much here. So we’re going to use it because it’s by far the better solution.”

That solution involves a better energy density vs. electric or hybrid-electric and no greenhouse gas emissions.

In CAeS’s approach, a hydrogen fuel cell powers an electric motor. This approach mitigates the production of Nitric Oxides (NOx), setting it apart from hydrogen-fuelled turbine engines.

However, Kavanagh acknowledges that hydrogen-electric fuel cell technology has its limits. For the foreseeable future, it may not be economically viable for aircraft exceeding 96 seats. This limitation aligns with Airbus’s exploration of 100-200 seat hydrogen combustion aircraft to be in service by 2035, a separate endeavour that does not compete with CAeS’s vision.

From 9 to 100 seats in four steps

CAeS envisions a four-step journey to get to 100 seats. The first two steps involve retrofitting smaller aircraft, starting with the Islander. Steps three and four entail developing new aircraft from scratch, also marking the transition from gaseous to liquid hydrogen usage.

This comes as Kavanagh underscores that retrofitting has its constraints due to design and storage challenges, making it an unsustainable long-term business model. As a result, CAeS will work towards creating “an aircraft that gets the best out of the propulsion system.”

This vision underlines Phase Three of their strategy, targeting aircraft with seating capacities between 25 and 50. Phase Four, scheduled for around 2035, explores the 50-100 seat range, and CAeS anticipates partnerships with major industry players to achieve this objective.

Though Kavanagh admits that there are challenges — for example, in creating the necessary hydrogen infrastructure — she sees enormous potential in the newly merged company. “We think this product is going to be really successful”, she asserts.

Kavanagh’s approach reinforces some of the conversations we’ve had with other next-generation aircraft companies in both the hydrogen and electric aircraft space. They say that even if every project underway succeeds (which is unlikely), the supply still won’t meet the demand for non-fossil-fuel powered aircraft.